Earlier today, I attended my mother-in-law’s funeral. Right now, I’m sitting in a Louisville airport lounge waiting to board my Delta flight to Atlanta, connecting to Charleston. Bloody Mary or ginger-ale? I’ve got a concert to play in Charleston in a few days, and jet lag has slapped me silly. I feel slightly stoned (jet lag is one of the only chemical-free highs), a little lonely, and relieved that I’ve made it this far on three hours of sleep. I get foot cramps when I fly, and often wake out of a deep slumber and dance the midnight tango to make them go away. Last night was such a night.

Yesterday’s fifteen-hour flight odyssey from Germany to Kentucky culminated in an overnight stay at a Louisville hotel overlooking the viscous water flooding the banks of the Ohio River, a surprisingly nutritious (quinoa and veggies) breakfast in a restaurant called the Whiskey Corner, and a perilous Uber ride with Chuck the driver to the Southern Baptist church where my mother-in-law’s service took place. Visitation, open casket, a spray of pink flowers to match her suit jacket, an enthusiastic choir, and a compassionate crowd of well-wishers and family friends—a classic Baptist funeral befitting a preacher’s wife, with all the bells and whistles.

Due to my husband’s recent illness and subsequent inability to handle a transatlantic flight at this point in his recovery, I volunteered to show up at the church as the Designated Mourner on his behalf. It was an easy call, since I knew I would be stateside for my concerts. I’ve read about Chinese funeral rituals where strangers are hired to sit in the second pew and sob loudly, but that wasn’t my gig today. No sobbing. Instead, I played the Pachelbel Canon in D, which is evidently the only piece in my repertoire that anyone wants to hear. Vineyard weddings, formal funerals, baptism lunches, cocktail lounge birthday shindigs, formal concert halls, Buckingham Palace—I’ve performed the piece in just about every venue imaginable. I even played it outdoors on a stage in a park while my audience watched silent fireworks. My mother-in-law once referred to the Pachelbel Canon as the Taco Bell Canon. I like that. Music for the people. Soothing, reliable, familiar. Maybe that’s what Johann Pachelbel intended. I was honored to play it one more time, for her.

It was a good-sized house for the funeral of a ninety-seven-year old woman, who had, by the time she died, lost her husband and most of her church friends. She lived a charmed life, protected by her God and well taken care of by her brave husband and loyal daughters. She slipped away the way most of us would prefer to exit this world—in her sleep. At the funeral, we sang her favorite hymns, listened to glossy stories about her century of exemplary life choices, and recited some prayers, the faded words of which seemed both appropriate and sad.

Note: All songs in the Baptist hymnal are written in keys for male singers.

The preacher invited each of us to stand and say a few words, so I did, because, as Designated Mourner, I thought my husband would want me to do so. I thanked her for raising a son who had become a loving husband, engaged father, a man who knows how to respect women. His mother might have happily played the part of the southern belle, but her accidental feminist edge occasionally revealed itself.

She first met Julia, our daughter, when Julia was thirteen months old. We had taken the long flight from Germany to Kentucky to present our precious child to her grandmother. I was distracted when we got out of the car because our four-year old son, cranky and hungry after the long trip, had just called his baby sister an asshole. He couldn’t pronounce it properly and said “sasshole,” but it was clear enough what he meant. Not exactly a good way to make a positive impression on one’s prim and proper Baptist grandmother.

“Why,” my mom-in-law said, in her charming Louisville accent, ignoring the sasshole comment and its perpetrator. “Julia looks just like me.”

“Oh, yes, I guess she does,” I replied. “Bless your heart.”

“But look, Robin, she does have your feet.”

She turned out to be half right. Julia, now twenty-three, looks very much like her beautiful grandmother, but she does not have my feet.

At the funeral service I played a decent improvisation of the Canon in D on a freshly tuned Steinway with a squeaky pedal and exited stage left. I picked up my suitcase and drove in a procession with our niece and nephew to Cave Hill Cemetery.

Our nephew helped carry the casket to the grave and I wept, not as the Designated Mourner, but as myself. I wept for her grandchildren, for my husband’s loss of his mother, for the trajectory of age and the oblivious way we march into the chasm of finality. One day you’re making French toast for your family, your kid is calling everyone a sasshole, and the future—with its endless opportunities to make good trouble—stretches out before you like an interminable game of hide and seek. The next day, it’s a spray of pink roses, a couple of hymns that no woman with a normal voice can sing, and a hundred resonating farewells.

She was buried next to her husband, and within spitting distance of Colonel Sanders. Muhammed Ali’s grave is also close by; she’s in good Louisville company. She believed in a heaven that features angels, a healed body, and a God who will always look out for her. May she be right. May the Canon in D be heaven’s soundtrack.

She was loved.

The air felt cold enough to break me in two, but the defiant sun shone fiercely on the end of an era.

**

People hover in the lounge, waiting for a chance to board the commuter jet—I’m sure it will be one of those planes with a dripping ceiling and seats with two and a half inches of legroom. Boarding begins for the privileged few. We, the great unwashed, stand patiently and listen to the over-worked gate attendant recite his endless list of elite pre-boarders—first class, business class, active military (thank you for your service), families with small children, disabled, economy premium, non-active military (thank you for your service) platinum card, gold card, silver card, bronze card, and more military (thank you for your service).

No one, and I mean no one, boards the plane in any of these categories.

“We’re pleased to announce a complimentary gate check of your cabin baggage today. Free of charge, we will gladly check your carry-on suitcase right here at the gate, and you can pick it up when you disembark in Atlanta.”

Does anyone fall for this? No.

“All other passengers may now board the plane.”

Finally. Like a pack of defeated, economy-class sassholes, we, the other passengers—also the only passengers—drag our weary selves onto the plane. No one thanks us for our service.

Drip, drip, drop.

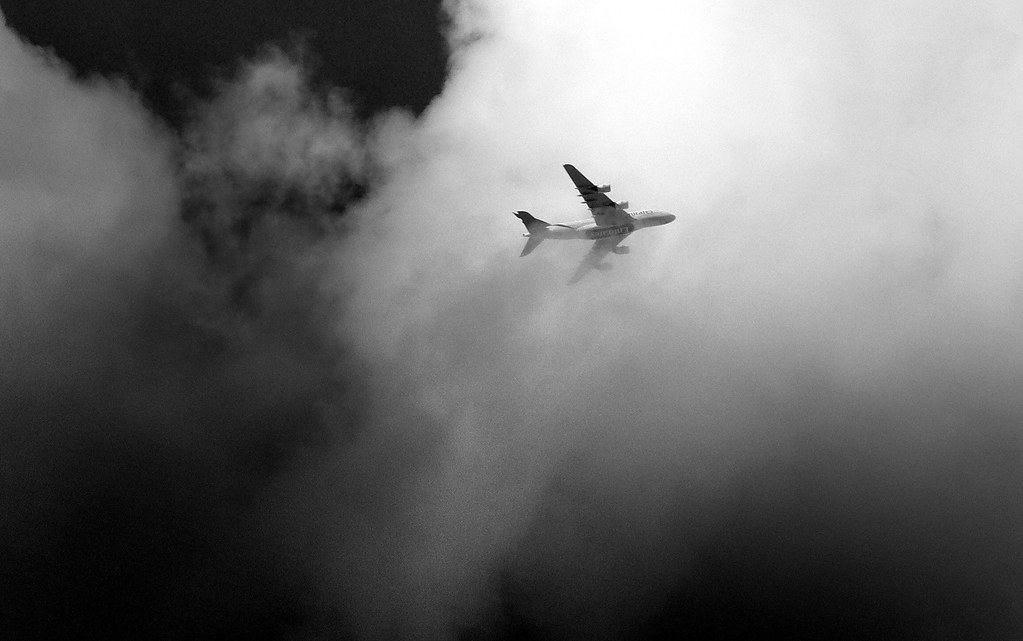

I ask a flight attendant about the dripping ceiling. I’ve encountered this on other domestic flights in the USA. I’m reassured that the drip is normal—a flaw in the air conditioning system. It’s February. In a few weeks all flights will be cancelled due to CoVid 19. We settle in, naively assuming that the perks and privileges of our peripatetic lives will go on forever, uninterrupted by disease, death, and the destruction of our planet.

The canned music on the plane, the calming pre-flight playlist that’s usually accompanied by static and security announcements, drones on for a few moments before I realize I’m hearing the Canon in D. Not my recording, but a soulless midi-synth-string interpretation intended to soothe our nerves as we prepare for flight. They’re making an effort. I hear the sound of a fake cello and drift off to sleep, right before the plane lifts into the air.