Excerpt from Piano Girl: A Memoir

Courtesy of Backbeat Books

©2006 Robin Meloy Goldsby

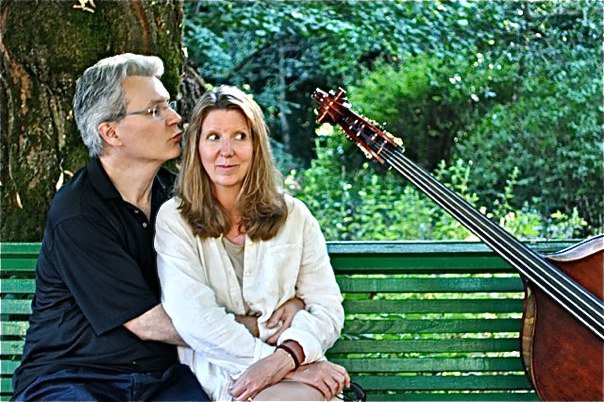

Okay, Ladies, listen up. Bass players make great husbands. There is no scientific data to support my claim. But having worked my way through the rhythm section, the technicians, and a handful of brass, reed, and string players, I’m a qualified judge.

First, consider this. A man who plays an upright bass is strong. He lugs the instrument around, carries it up steps, slides it in and out of cars, and maneuvers it through large crowds of people. If you marry a bass player you’ll be getting a physically fit husband. Okay, there is the occasional back problem. This crops up two or three times a year—usually when you want him to move your grandmother’s walnut armoire or need him to stand on a ladder and drill a hole in the ceiling. But you can cope with such minor inconveniences by calling a muscular clarinet player who is handy with a power drill. Good luck finding one. Here’s the thing: When your bass player is pain-free, he’s as strong as a bull. He has to be in order to make the gig. And he might even throw you over his shoulder and carry you over the threshold every so often, just because he can.

Next, ponder the shape of the upright bass. It’s shaped like a woman. A bass player knows about bumps and curves—he even likes them. He has dedicated his life to coaxing beautiful music out of voluptuous contours. He’ll do the same for you. Just don’t marry a stick-bass player, unless you look like Kate Moss or intend to spend the rest of your life eating lettuce.

Examine the bass player’s hands, especially when he’s playing a particularly fast passage. Now imagine what those fingers can do to you. Enough said.

A great bassist is an ensemble player, a team member who executes, with confidence, a vital role in any band with the strength of his groove, the steadiness of his rhythm, and the imaginative logic of his harmonic lines. This doesn’t just apply to the bassist’s music. It also applies to his outlook on life. A bass-player husband will be loyal, true, and interesting, and will help you emerge from life’s challenges looking and sounding better than you ever imagined. If you’re in a bad mood, don’t worry. He’ll change keys. On the other hand, if you marry a pianist, he’ll try and arrange everything and then tell you what your disposition should be. If you marry a guitarist, he’ll try to get ahead of you by analyzing your temperament in double-time. If you marry a drummer, it won’t matter what kind of mood you’re in because he’ll just forge ahead with his own thing. A bass player follows along, supports you, and makes you think that everything is okay, even when the world is crashing down around you.

There are some minor drawbacks. You need to have a house with empty corners, especially if your husband owns more than one upright bass. I know, you have that newly reupholstered Louis XV chair that would look fabulous in the corner by the window. Forget it—that’s where the bass has to go. You can come to terms with these trivial decorating disappointments by reflecting on the sculpture-like quality of the instrument. Even when it’s silent, it’s a work of art.

If you have children—and you will because bass players make great fathers—your most frequently uttered phrase will be “WATCH THE BASS!” You will learn how to interject this phrase into every conversation you have with your children. For instance: “Hello, sweetie, watch the bass, did you have a nice day at kindergarten? We’re having rice and broccoli for lunch, watch the bass, do you want milk or water to drink?”

You will be doomed to a life of station wagons, minivans, and SUVs. You might harbor a secret fantasy of zooming around town in a Mazda MX5 convertible, but this will never happen unless you go through a big messy divorce, give your bass-player husband custody of the children, and marry a violinist, which would be no fun at all. Better to accept the hatchback as an integral part of your existence and get on with it.

Any trip you make with your family and the bass will be a pageant that requires detailed organization and nerves of steel. In addition to your two children (one of whom probably wants to be a drummer—heaven help you), you will commence your journey with suitcases, bass, bass trunk, backpacks, amp, car seats, strollers, and diaper bag. Your husband, weighted down with an enormous backpack and a bass trunk the size of a Sub-Zero refrigerator, will leave you to deal with everything else. As you try to walk inconspicuously through the airport terminal, people will point and stare.

First Spectator: “They look the Slovenian Traveling Circus!”

Second Spectator: “Hey buddy, you should have played the flute!”

Things like that.

You will learn how to say ha, ha, ha, stick your nose in the air, and pretend that you are traveling with a big star, which of course he is, to you.

Your bass-player husband will know the hip chord changes to just about every song ever written in the history of music. This is a good thing. Just don’t ask him to sing the melody. He might be able to play the melody, but he won’t sing it—he’ll sing the bass line. And, if you happen to play the piano, as I do, don’t expect him to just sit there silently and appreciate what you are playing without making a few suggestions for better changes and voicings. He’ll never give up on trying to improve your playing. But that’s why you married him in the first place. He accepts what you do, but he pushes you to do it better.

If you marry the bass player, you marry the bass. Buy one, get one free. Your husband will be passionate about his music, which will grant you the freedom to be passionate about the things you do. You might not worship the bass as much as he does, but you’ll love the bass player more every day.

***

Robin Meloy Goldsby is a Steinway Artist. She is the author of Piano Girl; Waltz of the Asparagus People: The Further Adventures of Piano Girl; Rhythm: A Novel. New: Manhattan Road Trip, a collection of short stories about (what else?) musicians. Go here to buy Manhattan Road Trip.

Robin’s music is available on all streaming platforms. If you’re a Spotify fan, go here to listen. NEW! Listen to the Piano Girl Podcast. Stories, music, fun. Play the piano? Check out Robin’s solo piano sheet music here.

Personal note from RMG: Here’s a gorgeous playlist featuring my favorite “gentle music” players, including Ludovico Einaudi, Robin Spielberg, Christine Brown, Yiruma, Liz Story, et moi. I’m really proud of this playlist and hope it will bring you peace and joy. Right now would be a good time to listen. Twenty-three hours of solo piano! Click here to listen on Spotify or Apple Music.