(In loving memory of Emilio Delgado.)

Kids and drunks have a lot in common. They’re brutally honest, totally unpredictable, and anxious to be noticed, even if it means jumping up and down on a red velvet seat and pouring the remains of a beverage down the collar of any guy who happens to be in fun’s way. With this in mind, it’s not such a stretch for me to go from lounge pianist to musical director of a touring Sesame Street show.

I’ve done kids’ shows before, as an actor. I played Tanya Baum the Talking Christmas Tree at a “wake up Santa Claus” breakfast in Pittsburgh. And I’ve worn so many Easter Bunny costumes in department stores that it’s hard for me to go through the revolving doors of Bloomingdale’s without hopping. I once had a Valentine’s Day job at the Pittsburgh branch of Saks Fifth Avenue dressed as Cupid—I wore a red leotard with wings and ran around the store shooting foam-rubber arrows at customers with kids.

In the late seventies I donned a full-body Winnie the Pooh suit and marched in a parade to greet Santa Claus as he parachuted into the parking lot of the South Hills Village shopping mall outside of Pittsburgh. As the official parade marshal, I was scheduled to ride in a big red fire truck in my Winnie the Pooh costume. Not surprisingly, there was a fire that day and the truck canceled.

“No problem,” I said to the promoter. “I can walk the parade route.” I didn’t want to disappoint all those kids. So I marched in front of an eighty-piece high school marching band. I started off strong, but the parade route was long. Very long. Those big steel Pooh boots got heavier and heavier as we neared our destination. I could see—but just barely—through the honey pot on the head of my costume. I heard Santa’s airplane circling around and around. It became increasingly difficult to put one foot in front of the other. I couldn’t get enough air. I still remember the sensation of the trombone slides nudging me in my back, getting closer and closer as I dragged my legs and tried to wave at the throngs of kids lining the mall parking-lot parade route. My vision grew dark around the edges and my ears started to ring. Next thing I knew, my knees were buckling and I was sinking to the concrete. I had hyperventilated and passed out, causing a high school marching-band pile-up behind me. The drum major and two women from the marketing office carried me back into the mall before they took off my Pooh head.

“You really should have gotten her out of the suit immediately,” said the doctor examining me. “It’s very dangerous to be in one of these costumes for more than fifteen minutes.”

“Well,” said the promoter, who was nervously looking out of her office window. “We didn’t want the kids to know that Winnie isn’t real.”

“What?” said the doctor. “Better they should think Winnie is dead?”

Didn’t matter much. Santa missed his parachute target and got tangled in an oak tree at a gas station across the highway. It was a traumatic day for those kids.

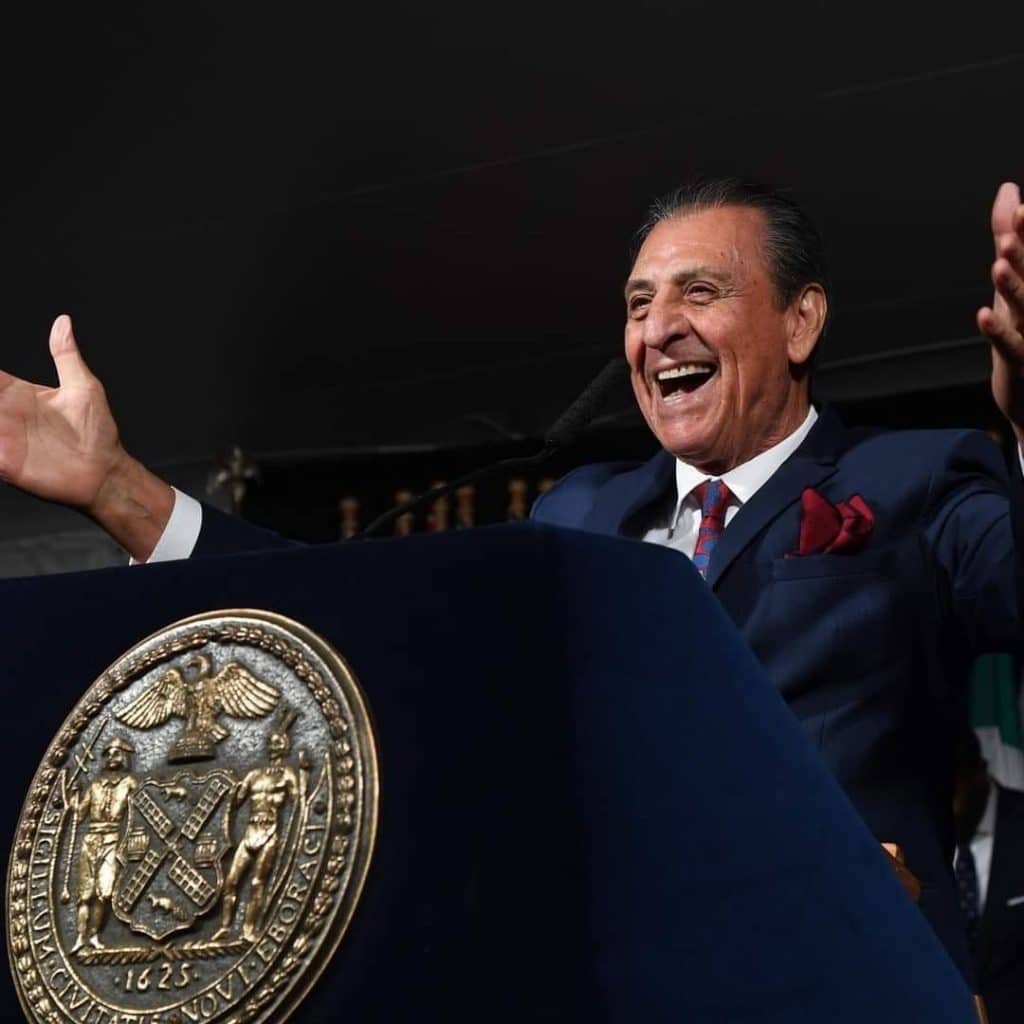

When Emilio Delgado—Luis on Sesame Street—calls to ask if I’m interested in being the musical director of his show, the first thing I ask is, “Do I have to wear a Muppet suit?” After my Winnie-the-Pooh fainting episode I’ve sworn I’ll never again wear another big furry costume with a twenty-pound head and lead boots. No way am I going to play the piano in a Cookie Monster outfit.

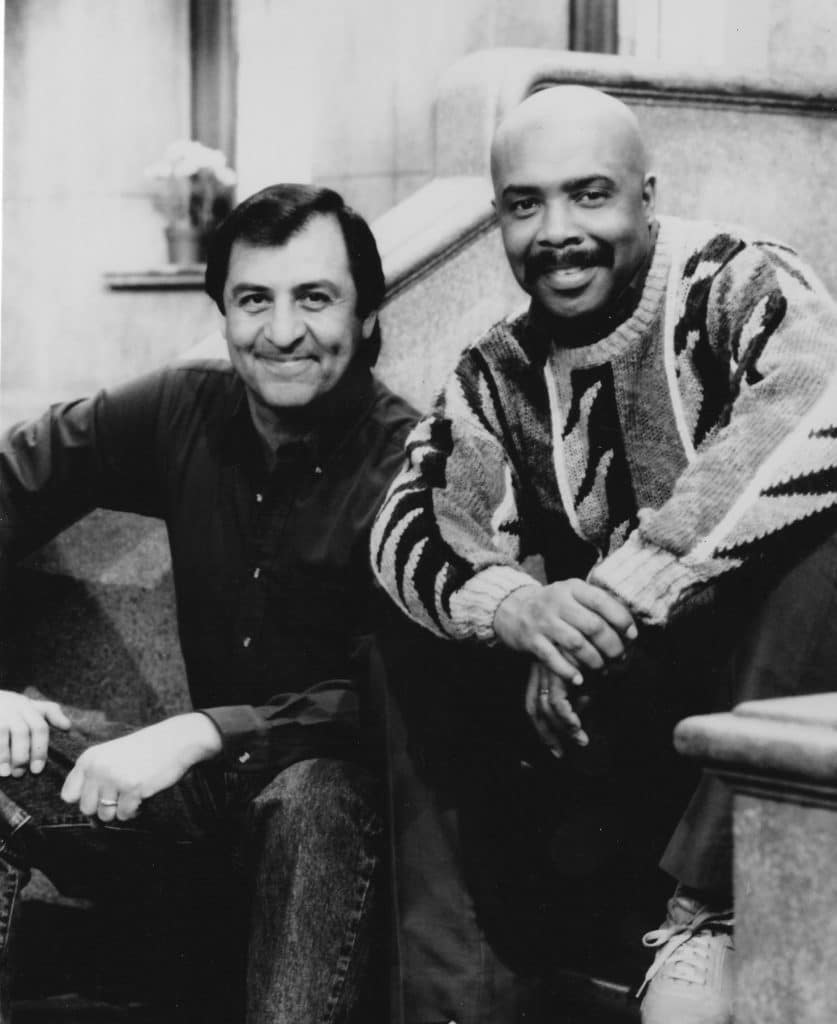

“No!” says Emilio. “You’re thinking of the Sesame Street Live show. That’s the Muppet show. My show only involves Roscoe Orman—the guy who plays Gordon—and me. And you on piano, if you want the gig.”

“But you said musical director,” I say. “Is there a band involved?”

“No,” says Emilio. “You would just be directing yourself. And us.”

“Oh,” I say. “I think I could do that. What’s the tour schedule? I’ll have to take time off from my Marriott job.”

“We’ll go out maybe one weekend a month. Sometimes more, sometimes less. The money is good, and I’m sure we’ll be treated very well. There’s just one catch.”

Here we go. There’s always a catch. The last time someone told me there was a catch to a piano job, I’d ended up topless in a Boston dinner theater with policemen and attack dogs in the wings.

“We need you to warm up the audience before the show starts. You know, do a little stand-up comedy routine and then move over to the piano and get the kids singing.”

“Oh,” I say. “I can handle that.” I envision us in school classrooms, with thirty attentive children sitting with their sweet little hands folded neatly on their tiny desks.

One month later I find myself in Frankenmuth, Michigan, at the Frankenmuth Bavarian Festival, wearing an orange baseball cap and hightops, standing backstage getting ready to run out and tell jokes to 1,500 screaming children. Gordon and Luis are big stars. Kids have come from all over Michigan to get a chance to see them in person.

I watch from the wings as three children leap onstage and play a game spitting ice cubes at each other. The first waves of doubt creep over me.

You’d be much better off in the bear suit, says Voice of Doom.

I run onstage and start the show.

As the daughter of a Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood musician, it’s ironic that I’m playing for a Sesame Street production. But though the two shows are completely opposite in their philosophies—one stimulating and aggressive, the other calming and gentle—they share a love of music and an awareness of the importance of music in a child’s development.

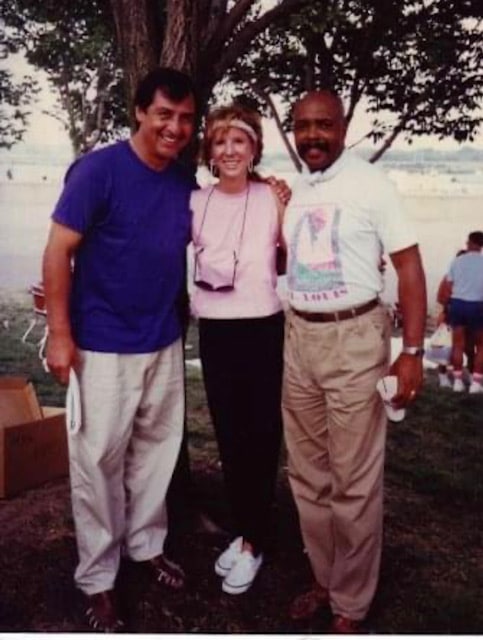

Emilio Delgado and I attend the same acting class—two working professionals trying to better ourselves by studying the two-year course in the Sanford Meisner acting technique. We’re friends and acting partners, spending long hours together rehearsing impossible scenes, and doing acting exercises that tap our emotional resources and usually result in either fits of laughter or trails of tears.

Emilio and his beautiful wife Carole come to my Marriott gigs or anywhere else I’m playing. They’re quite a pair, Emilio with his dashing Mexican good looks, and Carole, a lithe blond who can’t decide if she wants to be Margaret Mead or Lovey Howell. I turn on the TV in the morning and watch Emilio sing (as Luis) about the number “5.” I laugh out loud at his antics with Big Bird and his rendition of “La Bamba” with a herd of Muppet sheep singing baaaa, baaaaa, baaaaamba.

But both Emilio and I want more from our careers. We want to be challenged, to be stimulated, to follow a more artistic path. So we torture ourselves in acting class trying to get out of our creative ruts. I don’t want to be just a piano player—I want to do modern American drama. He wants to do film. We end up doing Sesame Street Live with Gordon and Luis.

Pasting together a live kids’ show, especially for such large audiences, means scrapping our adult concepts of entertainment. We start from scratch, trying to remember what it’s like to be five years old. Being quiet and gentle and singing hushed songs about love and family values? Those things function brilliantly in a small classroom or on a television set. But in a theater packed with 2,000 spirited children and their stressed parents—no way.

My job at the beginning of the show is to get the kids to guess where Gordon and Luis are hiding. After we exhaust all the usual possibilities—under the kids’ seats, in their mothers’ purses, in their neighbor’s ear, I go into the audience with the microphone and ask for suggestions to get Gordon and Luis to come out of hiding. I have a notion that one of the kids will say “music!” But the kids have other things in mind.

“Gordon, if you don’t come out, I’m gonna rip my sister’s hair out.”

“Luis, if I don’t see you in one second I’m gonna slap Timmy in the face with a wet washrag.”

“Gordon, if you don’t show up, my Dad’s gonna sue you.”

“If you guys don’t get out here soon, I’m gonna kick this microphone girl in the knees.”

“How about music, kids?” I say.

“It smells like sweat socks in here.”

“Gordon, I bet you’re on the potty!”

“Luis, come out or I’m gonna tell Santa you’re a jerk.”

“How about music, kids?” I say once again as I leap over to the piano. I get them clapping in time, tear into the Sesame Street theme song, and Gordon and Luis charge from the wings as the kids cheer and sing along. Many children wonder how Gordon and Luis have gotten out of the television set.

In the beginning we try, we really do, to do a variety of music, alternating up-tempo audience participation sing-along and dance numbers with poignant ballads about love and sadness. The ballads are a disaster. Both Gordon and Luis have gorgeous voices, and there is a ton of great music from the television show that we would like to do. But the same thing happens every time Gordon or Luis try to sing something slow. Halfway through the song, members of the pint-sized audience get distracted. They crawl under their seats, hit their neighbors, and cry out of boredom. Every singer’s worst nightmare.

At a beautiful concert hall in Calgary, when Roscoe goes downstage to sing a wonderful ballad called “Family” there’s a huge ruckus in the first few rows. Roscoe sits on the edge of the stage for this number in his casual “get down on their level” pose. “There’s more than only one way for a family to be,” he sings in his deep baritone.

Not even four bars into the song, a bucket of popcorn flies up into the air. Three or four kids start bawling. A mother drags a couple of the offenders up the aisle. Another kid screams, “Sing the doggie song!” and everyone claps and laughs. I see a tennis shoe soar through the light from the spotlight and land a dozen rows back. A ten-year-old boy jumps up and throws the shoe back where it came from. Three or four kids begin chasing each other up and down the aisles, trying to retrieve the shoe.

Really, it’s not all that different from the Atrium Lounge at the Marriott Marquis.

Through all the commotion, Roscoe maintains his concentration and continues singing, “You could have a brother, a sister, an aunt . . .”

One of the silver helium balloons attached to our set gets loose and floats up to the ceiling of the theater. While continuing to pound my way through the ballad, I look out at the audience. Not a single eye is on Gordon as he forges ahead to the big dramatic ending of the song, “Oh, oh, family, family, family . . .”

The audience has been hypnotized by the balloon, and they’re still sitting there, heads back, mouths open, looking at the ceiling when Roscoe finishes the piece. Luis and I have to force the audience to clap for him. We move on to “The Doggie Song.”

“Robin,” says Gordon after the show. “No more ballads for me. Did you see what happened out there?”

“Yeah,” I say. “Unbelievable. The chase thing with the shoe was terrible. And then they couldn’t stop watching that stupid balloon.”

“What balloon?” says Gordon.

“The one everyone was watching while you were trying to sing.”

“Oh, I didn’t even notice that. The whole time I was singing there was this little kid in the front row bugging me. He had scissors with him and he was cutting up little scraps of blue paper and putting them on my shoes. Then he started going after my shoelaces.”

“Oh. That must have been, uh, annoying.”

“Yeah. No more ballads. Enough is enough.”

Everyone has their limits.

It takes a few months of trial and error, but eventually we’ve got a nice show. We adjust to the constant buzz buzz buzz that lives inside theaters filled with preschoolers. There’s a lot of positive energy and power in these young audiences, and it’s a blessing to be part of it. I travel all over North America with Gordon and Luis. We’re quite a representative trio: the Mexican American, the African American, and the blond American. Gordon and Luis are swarmed at airports by starstruck stalker moms and their kids. They sign autographs and have their pictures taken with four-year-olds from Seattle to Atlanta. I stand off to the side and observe as the two men perform their public-television celebrity duties with grace and good humor. Then the three of us climb into an airplane and wing off to the next city, the next hall, the next zealous group of kids that will allow us, for sixty minutes, to share their fun.

It’s an honest job, and I love every minute of it.

***

In loving memory of Emilio Delgado.

Robin Meloy Goldsby is a Steinway Artist and popular solo piano streaming artist. She is the author of Piano Girl; Waltz of the Asparagus People: The Further Adventures of Piano Girl; Rhythm: A Novel and Manhattan Road Trip. New from Backbeat Books: Piano Girl Playbook: Notes on a Musical Life

New music from Robin Goldsby: