On the day I fly home for my brother’s memorial service, the boarding area at Frankfurt International Airport looks the set of a Broadway musical. Not a glitzy Hugh Jackman extravaganza with feathered chorus girls and a mirrored backdrop, but a bleak, throbbing production with a malfunctioning smoke machine, no singable melody, and an obtuse plot. In today’s cast of characters are a cheerless Balkan basketball team, several homeward-bound military families, backpacked German tourists, and assorted businesspeople. We’re all wearing some version of athletic-wear or pajamas, except for the businesspeople, who sport blazers over their yoga and jogging pants.

Our flight is headed to Detroit, where most of us will shuffle or hustle through the terminal to snag flights to other cities. I’ll be connecting to Pittsburgh, home of the Steelers, the Pirates, the Penguins, and the Rawsthornes (my family).

A beer-bellied man in the departure lounge wears cargo shorts and a t-shirt that says “sex addict.” Like so much in the modern world, travel has become an exercise in maintaining one’s dignity—maybe respectable costuming would help. My eighty-eight-year-old mother tells me that passengers once dressed elegantly for air travel. A woman wore gloves and a hat that matched her travel ensemble; a man wore a suit (hard pants!) and real shoes. I do not pine for the days of stretch-less clothing and stiletto heels, but I reject the notion of dressing for a day trip to Sea World while on an international flight.

I spy a family of redheads: two parents with six children under the age of ten traveling with an enormous amount of carry-on luggage and a pair of those creepy, hairless cats. Animal lover that I am, I should call the kitties cute and leave it at that. Not cute. The kids, with their flaming halos and Bugs Bunny logo-shirts, are cute, but they might be trouble because all kids are trouble on long-haul flights. The parents look shell-shocked. Their combined airfare is at least 10K, and that’s without the cat tariff. Where are they going and why? A vacation? A travelling family band? I think not. Moving?

Perhaps, like me, they are flying home for a funeral. The cats whine; the kids perch on top of suitcases stacked in a neat row on the lounge floor; the parents watch over the lot of them, resigned and slightly morose—an army of depressed Weasleys.

My brother, Curtis Rawsthorne, was also a redhead of sorts; he had strawberry blond hair and blue eyes. He died in January at age fifty-nine. It is now June. We have scheduled the memorial six months after his death because my parents needed time to process their crushing grief. Every second person in our family had suffered a bout of Covid through the winter months. Plus Pittsburgh snowstorms, at their January finest had pummeled the not-so-Golden Triangle. Back in the heart of winter, June seemed like it would be a more fitting time to celebrate his life. Curtis was, in his youth, a boy of summer. Baseball, beaches, butterflies.

And then there were two. With the death of our brother, my sister, Randy, and I are the leftover kids. Randy lives in Panama where she volunteers as a coral restoration scuba diver. After dealing with her own international flight trauma-drama, she will meet me at the memorial venue—a lovely country club where our brother worked in the kitchen—and the two of us, travel weary and bleary-eyed, will attempt to guide my parents through the aftermath of their tragedy. I’m not sure there’s enough love to help them through this, but we, the leftovers, shall try.

I hope I’m not sitting anywhere near those redheads. I’m not enthusiastic about a romper room rebellion halfway over the Atlantic. That sounds like a lack of compassion for the parents of small children, but I’ve paid my dues flying with my own unpredictable toddlers over the years. Who can ever forget the exploding diaper incident, or the time my eighteen-month-old son morphed into Robert DeNiro (think Cape Fear) on a flight to Frankfurt? I should have been banned from all European airports after that episode. This time around, I’ve paid a goodly sum to sit in the Premium Peasant section of the plane—the area of economy seating reserved for those too thrifty to buy a seat in business class but upscale enough to want to pretend.

I’m an American living in Cologne, Germany. I’ve been overseas since 1994. My inner circle of friends includes a dynamic, bad-ass group of international women. We came here for work and love, to escape political madness, to absorb European culture, to raise our families with an elevated quality of life. This works out beautifully, until someone we love grows ill and dies and we’re a million miles away.

Here’s what no one told us when we moved to a distant land clutching a big bag of youthful dreams for our future: One day, members of our original tribe—our oldest friends and family members—would begin to die, and we would be brought to our aging, creaking knees by the emotional distance we must travel to get back home.

Expat Americans don’t have a franchise on travel woes, especially when it comes to bereavement flights. But it seems worse when flying home from overseas. Maybe it’s the ocean, the time change, or the jet lag—or maybe it’s the thud in our stomachs when a surly and suspicious American immigration officer looks at our US passports (and foreign residence permits) and says, insincerely, “Welcome home, ma’am.”

I really hate that.

Boarding begins. The long list of priority passengers makes me crazy. First class, business class, the Olympic-sounding gold-silver-bronze medallion travelers (good thing they’re all dressed in athletic clothing), the Sea-World bound self-proclaimed sex addict, families with small children and hairless cats, US military personnel (thank you for your service) and finally, the rest of us. The airline might as well call us the Great Unwashed—we hover in the lounge as an airline official attempts to convince us to gate-check our carry-on luggage, an action required because the medallion people and the redheads strolled onboard with a thousand small suitcases and large paper sacks.

As I skulk into the long, gray, optimistically named “skyway”—the sloped tube that leads us onto the plane—I recall the time our toddler daughter threw herself on the floor and rolled her way to the plane’s door. We were running late, and my husband suggested she hurry. Those were the best old days, when our family boarded planes to reach a sun-kissed vacation, an overdue family reunion, or an exotic job opportunity. Days of wine and roses and diapers and new life and adventure. We rolled on dirty carpets without fear.

It seems like no one died back then. We concerned ourselves with births, education, making a living, creating art, seeing the world, drinking martinis, and dining in exotic European restaurants that featured olive trees, lavender, and gnarly French chefs who put bacon in the vegan salad. Our lives seemed glamorous and vital, peppered with nonchalance, as we bumbled our way through the world’s airports and train stations with too much luggage, a stroller, and (bonus points for difficulty) a double bass trunk the size of a Subzero refrigerator. We were glamorous and vital and delightfully confused. Now, in our mid-sixties, just when we have come to our senses and figured out how to live without unnecessary drama, our parents and siblings and friends are dying. WTF.

My brother died before my parents, a tragedy that wasn’t in my midlife playbook. My friend Raquel says that being in your sixties is like being thirty-seven weeks pregnant—there’s no going back and anything can happen at any time. Anything can happen.

In the skyway, I stay six feet away from the person in front of me—leftover Covid regulations stick to me like gray hair on a black sweater—but the maskless man behind me breathes down my neck. It’s late morning and he smells like popcorn and stale beer. Maybe I should hit the ground and roll.

I don’t recall flying anywhere with my brother. We saw much of the USA from the bug-splattered windows of a wood-paneled Plymouth station wagon. We laughed at my dad’s jokes, squabbled over who got the window seats, and ate fast food hamburgers with extra pickles. My brother, the youngest in the family, was our golden boy. During one cross-country trip in 1973, Randy and I spent six weeks with him bouncing around (no seatbelts!) on the bench seat of that Plymouth. Like the redheads in the back of today’s plane, we never questioned our destination; we went along for the ride and counted on some fun along the way.

I fantasize about an airline that caters to those of us flying home for funerals. A flight of fancy, so to speak.

“Now boarding,” says Helen Mirren, our flight attendant and grief counselor for the day. “Now boarding all passengers who have recently lost family members or close friends. Everyone else, please step aside for the red-eyed Sorry People as we carry them onto the plane.” Helen would place us in beds with fluffy cashmere blankets and give us noise reduction headphones tuned to streaming platforms that play ocean sounds or Yo-Yo Ma interpretations of Bach Cello Suites or whatever music soothes us.

“During our flight today, we offer fresh ginger tea along with light tranquilizers. Feel free to request your international comfort food of choice. This afternoon we suggest organic mac ‘n cheese and mashed potatoes, with adjustments made for dietary restrictions and allergies. Vanilla cake with just enough frosting will be served before landing.”

Five-star luxury for fifty-star grief. None of this would help. Death is death is death. Eventually we lose everyone we care about. Or they lose us. It’s the economy-class tariff we pay for the first-class privilege of love.

Back to reality. I have an excellent seatmate—a handsome young man named Sebastian with a growing family and a thriving business. He’s physically fit and even smells good—no small thing for those of us who have occasionally been seated next to a sweating, man-spreading passenger with a stinking sack of greasy fast-food. Sebastian and I talk just enough—I tell him about my brother and he expresses his condolences—and then we return to our books and laptops. Premium Peasant class seems to be working out just fine.

My brother, who was both knowledgeable and curious about world politics, never visited me in Europe. Our lives and interests drifted further apart as decades passed—our shared history decanted into an annual restaurant visit arranged by my parents, who enjoyed seeing their three children together sharing a meal.

During the flight I make my way to the rear of the plane to use the facilities, an act that requires confidence, hand sanitizer, and the ability to karate-kick the flush button with one leg while balancing on the other. Three of the redhead children writhe on the floor in front of the door to the toilet cabin. Making their own fun, they’re playing some sort of lizard game with toilet paper. They roll around on their bellies while growling “gotcha!” Someone is going to have to dip those kids in a vat of disinfectant upon arrival. The two cats, whose cages balance on the seats vacated by the squirming kids, are mewing rhythmically—a C-sharp feline metronomic wail. The parents, wearing sleep masks and earplugs, are comatose, and who can blame them?

I step over the squirming kids and return to the Premium Peasant section of the plane. I have organized the memorial program for my brother, a task that’s within my skill set, although not one that I’ve ever attempted with this much oversized baggage. I go over my eulogy and song list (I’ll be playing the piano as well as speaking) and glance again at the rundown for the thirty-minute program. It makes me sad—my brother’s life condensed to a thirty-minute program of storybook memories. Just enough frosting.

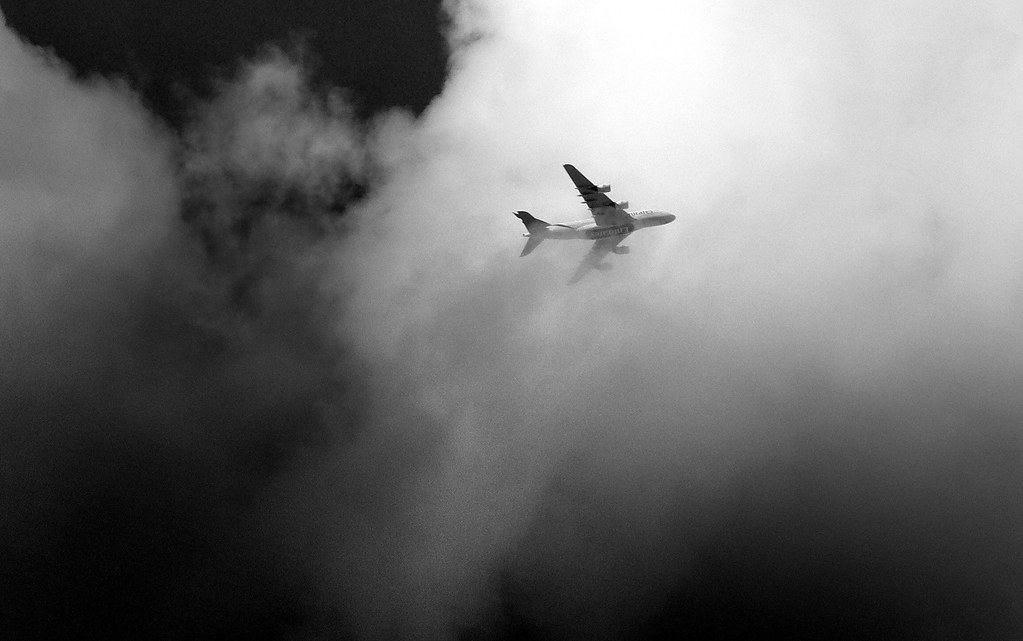

Fly the friendly skies. I look out the window. The buoyant cloud fluff and cottony wisps of light give the impression of peace, but the interior of the plane is far from tranquil. We are 300 humans—or souls as the airline industry likes to call us—slingshot from one continent to another, as some of us attempt to recapture and honor the lives we’ve left behind. I feel temporarily caged by my glorious, golden freedom to choose where I live and wounded by love, patriotism, and melancholy.

Distance and death do not pair well with grief and guilt. Expat grief is unique; we’re forced to face loss with an extra dose of grit to get where we need to go as quickly as we can. When someone we love dies, we crave the permanence of our roots, the comfort of shared history.

My European friends are my greatest sources of compassion and kindness, but they’ve never heard the distinctly American crack of my brother’s baseball bat at a Pittsburgh field on a sweltering August day, or experienced the unique way my brother, sister, and I laughed, danced, and squabbled our way through a popsicle-filled, pie-throwing, pool-splashing carefree Pittsburgh childhood during a decade when such a childhood was still possible.

Death is a cruel maestro. My brother’s death means I’ve lost another piece of my personal history to the Orchestra Invisible, my not-so-secret symphony of loved ones who call to me, one of the leftover children, from the mysterious place where songs are born.

This is not my first transatlantic funeral trip, and it won’t be my last. I’m still waiting for comfort food when the flight crew tells us to prepare for landing. I hope the redhead kids, the hairless cats, and the parents—especially the parents—are securely buckled in their seats. Arrivals, like departures, can be bumpy. The redhead family is still too young to know it, but anything can happen.

***

In loving memory of Goldsby’s brother, Curtis Rawsthorne.

Robin Meloy Goldsby is a Steinway Artist and popular solo piano streaming artist. She is the author of Piano Girl; Waltz of the Asparagus People; Rhythm: A Novel and Manhattan Road Trip.

New from Backbeat Books: Piano Girl Playbook: Notes on a Musical Life