Whenever I visit Paris, I want to be a tourist. I want to fall in love. I want to be enchanted. I want magic and romance and art and a big crusty baguette. I crave the silvery slanted light that seeps over the horizon in late morning and clings to the edges of the city until sunset. If I’m not actually in the Eiffel Tower I want to be staring at it from a distance, watching, in the early evening, as it sparkles like the world’s largest bottle of champagne.

I know Parisian food can be overpriced, French fashion can be overrated, and snootiness often underscores daily life. I know the political situation in France leaves much to be desired; racism and the nationalistic tendencies of some citizens pull on the frayed sleeves of others. I know these things, but still I cannot look away from the golden patina of the city itself. The city glows. I walk through Paris in my somber black clothes, like I’m trying to absorb a bit of the city’s smoldering blush. If only.

I’ve been to Paris seven times. Here are some jumbled notes from those visits :

1977: Pittsburgh to Paris

My college roommate, Debra, and I attend Chatham College for women, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. We have been in London on a study trip for the last six weeks and feel a strong desire to visit Paris. Who knows when we’ll be this close again? Between the two of us we have twenty four dollars. Off we go. Allez!

In Paris, we stay in a hotel with a bidet in the room and a toilet down the hall. We think the bidet is a place to wash our undies (that’s one way of looking at it). So we dutifully rinse our panties and socks in the bidet every night, impressed by French plumbing. Madame, a stout woman with a severe face and a demi-beard, serves chocolate croissants for breakfast. I drink hot milk from a bowl and pretend I’m sophisticated. I feel far away from Pittsburgh.

We go sightseeing. We can’t afford admission to any of the museums, so we stay outside, shivering in the Jardin des Tuileries, and eating chocolate crêpes made with Nestlé Quik. We stare at the Eiffel Tower. We walk a thousand kilometers because the Metro scares us. Hiking through Paris can be a pleasure, but Deb insists on wearing red cowboy boots with five-inch stiletto heels. She bought them in London and hobbles through Paris looking like a Monroeville Mall hooker out for une aventure française. We say “ooh-la-la” and sing Jacques Brel songs until a smarmy man wearing tight pants and several earrings tries to grab Deb’s ass. In a rare act of physical revenge—I’ve always been a wimp—I punch the little guy in the nose and we run away, no easy thing in those cowboy boots. For many decades, Debra will claim I saved her life. Merci beaucoup.

Debra almost gets arrested when we pay tribute at the tomb of the unknown soldier under the Arc de Triomph and she inadvertently tramples on the tomb. Teetering on those red boots while attempting to take a snapshot of moi, she has backed up and stepped right onto the poor soldier’s grave, the spikes of her heels firmly planted over the commemorative plaque. A Gendarme in a spiffy blue suit—don’t we just love their hats?— screams, “Attention!” at her, along with other French invectives we don’t understand. I suspect he’s saying, “Get the fuck off the grave you idiot,” but who knows? When Deb attempts to flee, her stilettos catch between two cobblestones. Stuck! Eventually she frees herself and we exit the Arc stage left, our heads bowed in shame. A flame burns next to the tomb. We’re lucky she doesn’t catch on fire.

That night we pool our remaining funds and visit the Folies Bergère. We are seated in the last row—quite a climb with those red boots—right next to two American soldiers from the South Side of Pittsburgh, our hometown. “Wait till yinz guys see the babes,” they say, in perfect Pittsburghese. “Foxy!” I’m discovering that people from Pittsburgh lurk everywhere, even in block Y of a topless Parisian cabaret. Slack-jawed, we gawk at the naked dancers as they hang, upside down, from the bejeweled ceiling. We don’t have this kind of thing in Pittsburgh; certainly not on the South Side. Deb decides we need to add feathers to our college girl wardrobe when we get back home, something I’m sure will be a big hit at our feminist school. We eat several more Nestlé Quik chocolate crêpes and head back to London the next day.2003: Circus, Circus

We live outside of Cologne, Germany, skipping distance from Paris on the Thalys, a high speed train that whisks us through Belgium and into Paris in four and a half hours. Our daughter, Julia, is six; our son, Curtis, is nine. Short on cash, but desperate to get away for a weekend, we’ve booked a seedy hotel room above a Chinese restaurant next to the Gare Saint-Lazare. As transplanted New Yorkers, we should know better than to stay next to a train station, but we’ve booked late, we’re strapped for cash, and it’s Easter vacation, so we’re lucky to find anything at all.

We eat baguette sandwiches at the Tuileries, engage in a spirited conversation with a French pharmacist when one of the kids gets sick, walk up Montmartre to Sacre Coeur, listen to a cellist playing Mozart next to the cathedral steps, check out the gargoyles at Notre Dame, and spend many hours looking for an affordable restaurant for a family of four. We dodge pickpockets and dance between the raindrops. It drizzles almost constantly. I love Paris in the springtime, when it—oh, never mind.

Julia and I attend a free fashion show at Galeries Lafayette, presented under a stained glass dome on the top floor of the store. She laughs through the entire program, amused by the flashy ready-to-wear costumes, and charmed by haughty models who every now and then break character and smile at her. During the finale, when the models glide over the catwalk sporting bridal gowns that resemble spun sugar, Julia says, “Mommy, this is just like the circus.”

We visit a small park for children that features an amusement park, a dusty playground, and a petting zoo. While waiting in line for croissants, we meet a Chinese American family from Los Angeles. The kids ride together on a dangerous looking roller coaster that threatens to derail at every turn. John and I drink coffee and chat with the parents. They are staying in the Hilton, close to the Eiffel Tower. I think about the firetrap where we’re lodging and vow never to return to Paris until we can afford a decent place to stay. They leave the park in a taxi; we walk to the Metro. We promise to stay in touch, but we won’t.

We take the kids for a boat ride on the Seine. Look at those bridges! Julia pretends to pilot the boat. Curtis pretends he is traveling without parents.

We eat chocolate crêpes made with Nestlé Quik.

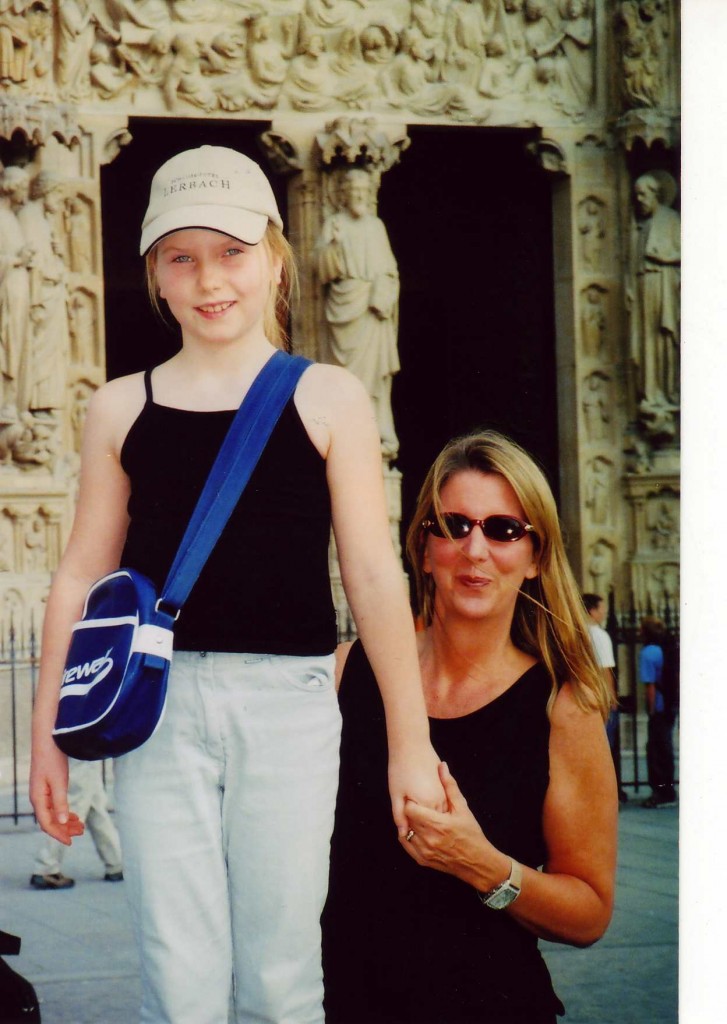

2005: Room with a View

Girls’ Weekend! Julia and I stay in a charming little hotel on Montmartre; a step up from our 2003 train station rat-hole. We have to walk up a steep hill to get to our digs, but it’s worth the climb. From our room, if we lean out the window and swivel our heads just the right way, we can see the Eiffel Tower. We drop our bags and head right over there, stopping for mousse au chocolat on the way. We climb to the second level of the tower and stay for two hours, watching the sun poke through storm clouds, spotlighting various landmarks. From our steely perch we plan the next two days; where we’ll go, what we’ll see. I’m determined my daughter will love Paris, that she’ll speak a little French some day, that she’ll soak up Parisian art and beauty and claim it as her own.

We visit the Louvre and Musée D’Orsay. We go to the Rodin garden and tour Notre Dame. Julia is nine years old and takes in the architecture and culture like a seasoned pro. She plans all of our trips on the Metro, circling stops on a paper map with a pink magic marker. After a day of non-stop tourist activity, she sleeps soundly in our little hotel room.

I discover we can go to Disneyland Paris on the train—for the bargain price of ninety euros, including train ticket and admission for both of us to the park. I’m not keen on confusing Paris with Disneyland, but our girl is nine years old and if not now, when? I don’t tell her where we’re going. We get off the train, she sees the pink castle, and doesn’t stop laughing the entire day. Mickey Mouse, it turns out, exudes even more charm when he speaks French. Goofy is another story, but you can’t have everything. We avoid the souvenir stands, eat lunch in the Pirates of the Caribbean restaurant—Jul is a little scared of the pirate waiter, who wears an eye patch—and watch French Tinkerbell descend from the Magic Kingdom castle. Is it my imagination, or is Tinkerbell wearing red lipstick? We take the train back to Paris, all the while singing “It’s a Small World” in French (Le monde est petit, après tout).

In a quaint restaurant in Montmartre Julia orders the children’s hot dog special, served with a kid-friendly combination of Roquefort cheese and sauteed onions. My American daughter scrapes off the goop, shrugs her shoulders, and says, “C’est la vie.”

2007: Marais, Meurice, Monet

Julia and I arrive in the Marais to meet up with our dear American friends, Carole and Emilio, who have rented a lovely little apartment in Paris’s most charming district. We stay in a hotel across the street.

All of us are on a tight budget, we go for long walks and boast about our ability to visit Paris without spending a fortune. The weather, for once, plays along, and we walk for hours. We ride on a Ferris wheel, people watch, and drink chilled white wine in the Tuileries. Julia needs a restroom, so we stroll into the Meurice Hotel. Carole, Julia, and I go to the ladies’ room, or the Queen’s Potty, as Jul calls it. We spend a bit of time in there, lounging and lolling about in velvet chairs, splashing cool water on our faces, repairing our lipstick and powdering our shiny faces. When we emerge from the Queen’s Potty, Emilio, who occasionally thinks of himself as Thurston Howell III, has snagged us a table in the bar.

“Emilio,” says Carole. “We can’t do this. It’s really expensive here.”

“Ah, come on, you only live once,” he says. Emilio is wearing an ivory linen blazer. He looks like he was born in this hotel.

I stay out of the fray—I’m too impressed by the hand painted ceiling and the jazz duo serenading us as we take our seats.

“You’ll be sorry,” says Carole.

The appropriately grumpy waiter takes our order. After consulting a menu (one without prices), Carole and I go all-in and request champagne with crushed rose petals. Not to be outdone, Emilio orders a mint julep, which seems a little odd for Paris, but he’s paying, so mint julep it is. Julia orders a 7-Up.

“We do not have the 7-Up,” says the sneering waiter. “What we have is like the 7-Up, but it is not the 7-Up.”

He brings a tray of olives.

“Do you like olives?” Carole asks Julia.

“Not really,” says Julia, who is still recovering from the 2005 Roquefort cheese incident.

“Well you better learn, because we have to eat everything they give us. At these prices we’ll have to skip dinner.”

Mademoiselle eats about thirty olives. The bill comes—130 euros for four drinks. And that’s with fake 7-Up.

The next day we take a bus to Giverny and visit the Monet gardens. We see Claude’s water lilies—the ones he planted and painted, the Japanese bridge he built and recreated on canvas, the cathedral at Rouen. I feel like I’m standing right in the middle of a Monet painting. It moves me to tears.

2009: Fusion Gypsy-Jazz Guitar, Toile du Jouy, and Bronchitis

I am finally in a five-star Parisian hotel with my husband, John. He will perform tomorrow night with Biréli Lagrène and the WDR Big Band. Sadly, John has a bad case of bronchitis and can do nothing but stay in the hotel room and try to get better before this evening’s sound-check and performance. So much for our romantic weekend.

What to do. I hate to leave John suffering and hacking away alone in our suite, but I don’t get to Paris very often, I’m here for the first time since 1977 without kids, and I don’t particularly want to waste a day in a dark room watching CNN weather reports or French game shows. Nor does John want me to hang around. He wants to sleep. So I head to the fabric markets and stare longingly at bolts of toile de jouy, decorating, in my mind, the Parisian flat I’ll never own. I buy nothing, but I entertain myself for hours by running my fingers over the cloth. I consider heading over to the Meurice for the crushed rose-petal champagne cocktail, but show restraint and drink Sauvignon Blanc with my lunch. I walk. The wind chills me, but I go for a boat ride—the ultimate tourist activity. Strangely, I enjoy being alone in the City of Love. I should do this more often.

I arrive back at the hotel just in time for the concert. Birelli, the genius guitarist, sounds great; so does John. A little bronchitis can’t stop a good jazz musician. The next day John and I arrange a trip a deux to the pharmacy, where we snag a grab bag of specialty medications with instructions we don’t understand. We eat extremely spicy Indian food, which John can’t taste, but I assure him it’s delicious even though my head is on fire. We travel back home on the train. We’ve booked our tickets separately, so he sits in first class with the band. I ride in coach, fall asleep, and dream about bridges and fabric.

2010: Les Garçons

I travel with two sixteen year old boys to Paris—my son, Curtis, and his South African friend, Chris. We sit in different parts of the train and stay in separate hotel rooms, but, since I’m the gal with the money, we meet for meals. I spy on them at various tourist attractions, and, with the help of a cell phone and Chris’s bright red scarf, I spot them in the Eiffel Tower, high up on the second level, as I sit in an outdoor bar on the bank of the Seine. I wave to the boys and one of them waves the scarf. There’s something beautiful about this, but I’m not sure what it is. The Eiffel Tower reminds me of a teenage boy—tall and strong, but delicate somehow. Fragile, robust, stretching up, up, and away.

2015: Free the Girls

As often as I’ve been in Paris, I’ve never performed here. Until now. I’ve been invited to present my Piano Girl concert program for the AAWE, an American women’s organization, at Reid Hall, part of the Columbia University Global Center in the Montparnasse district. My concert will benefit “Free the Girls,” a program that rehabilitates victims of human trafficking and prostitution.

Julia has come along with me. She has recently spent some time here alone, but this is our first Paris trip together since the 7-Up episode at the Meurice. The Thalys trip now takes only three hours from Cologne—the railroad officials have upgraded that pesky Belgian stretch—and we arrive at our hosts’ apartment in no time at all.

Deborah and John, Americans who have lived in Paris for over fifteen years, reside in a huge old Parisian apartment in the 17th Arrondissement. It’s one of those big places with a tiny elevator, high ceilings, velvet sofas, and a gazillion books. French shabby chic. I could move in and not change a thing.

Our friend Sallie lives in the Marais. She takes Julia and me to lunch at her favorite bistro. Julia’s hot-dog days are long behind her—she has been a vegetarian for eight years, so we eat braised vegetables, salad, and a pear and almond cake for dessert. Sallie takes us on a tour of the Marais, starting at the Place des Vosges. The sun shines and we see pale green buds on the trees. The Marais has become a tourist attraction in recent years, but Sallie knows her way around. She shows us secret pathways leading into hidden gardens, down winding streets, and past historic half-timber homes.

On this trip I try, as I always do, to speak a little French. I give up. There’s always next time.

Rounding the corner in the Marais, eight military policemen, in full riot gear and carrying machine guns, march past us, patrolling the neighborhood. Their presence is a result of the Charlie Hebdo massacre and subsequent siege at a Jewish supermarket. Later that evening, Deborah shows me photos of soldiers at her synagogue, in the days following the attacks.

“The soldiers are still patrolling,” she says, as she rolls her homemade chocolate truffles, one by one, in powdered sugar.

I have grown up here, without meaning to. Every time I return, I’m a little further along on my trek through adulthood. I’ve gotten lost in back streets, struggled with the language, and learned to negotiate Paris both with and without money. I’ve traveled here with a red-booted friend, with curious children, nonchalant teenagers, and a handsome (but coughing) husband; as a teenager, as a mom, as a wife, as an artist. I’ve watched parades and concerts and street performers and now, soldiers. I’ve been cold and wet and exhausted and hungry in Paris; anxious and sad; startled and astounded, amused and elated. Never once have I been bored.

Paris remains a place of beauty. Man-made beauty, with extremely good lighting. Really, the city is a wonder.

I play my concert. We raise money for “Free the Girls.” Julia sings. I play some more and tell a few stories. Applause. We take a bow. The audience’s warm embrace scrapes the chill off the early spring day. After so many decades of getting to know the City of Light, maybe now it knows me, just a little. Time for a chocolate crêpe.

Robin Meloy Goldsby is a Steinway Artist. She is also the author of Piano Girl; Waltz of the Asparagus People: The Further Adventures of Piano Girl; and Rhythm: A Novel.

Sign up here to receive Robin’s monthly newsletter. A new essay every month!

Photos provided by Carole Delgado and Julia Goldsby