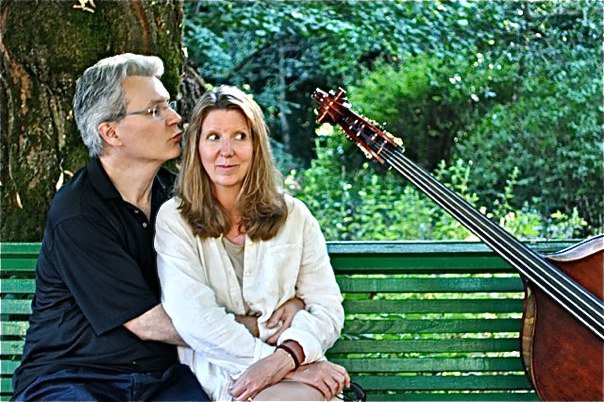

An Excerpt from Goldsby’s book Waltz of the Asparagus People [Bass Lion Publishing]

©2011 Robin Meloy Goldsby

Go right at the rotary and take the third exit, says Kate, the uppity British voice of our navigation system.

“What rotary? Where?”

“Like you can even call this a rotary,” says John. We’re in Villefranche sur Saône, France, a bit north of Lyon, searching for the home of Jean Auray, the award-winning luthier who has agreed to build John’s new double bass. Any good musician will tell you that a quality instrument is the extension of an artist’s soul, and John is looking to expand his soulfulness. Throughout his career he has dreamed of finding a bass that’s comfortable to play, with a warm, clear, punchy sound and consistent tone across its entire range.

Monsieur Auray’s home and workshop must be around here somewhere; Kate just needs to find it. We’re packed into our midsized car with two very tall teenage kids and the bass John currently plays, a factory-made German instrument built after World War II. Building the new bass will take the better part of a year and several meetings requiring trips from Cologne to Lyon, a drive that typically takes six hours. Today, with the French autoroute traffic, a break for lunch at a French Ikea, and numerous rest stops, it has taken us a bit longer. We’re a little cranky.

“Just about there!” I shout toward the back seats. Silence. With John’s German bass packed between the two kids, I cannot see them. For all I know Curtis and Julia jumped out of the car somewhere around Nancy.

“Mom, I’m thirsty,” says a muffled voice.

“Me too.”

“Just a few more minutes,” I say.

“They’ve got some nerve calling this a traffic circle,” says John. “It’s more like a triangle. Wait, that’s the third exit!”

“No it’s not, it’s the fourth. There wasn’t a third.”

“How can there be a fourth if there wasn’t a third?”

Take the third exit, says Kate. She is agitated by the French traffic regulations, or lack of them.

We drive around in a triangle-circle for a few minutes while we huff and mutter and blame each other for being lost.

Take the third exit, says Kate.

“Perhaps this is the French idea of a circle.”

“Maybe it was the best they could do at the time. You know, ancient city and all that.”

“Non,” says my husband, who is now speaking in a French accent, quite a party trick for a boy from Kentucky. “They were sick of the circle. They had a better idea. It is like a circle, only not a circle. It is a circle with corners.”

“Isn’t that called an intersection?” says Curtis from the back seat.

Please take the third exit, says Kate, using the tone of voice she assumes right before she resorts to the silent treatment.

“There, that’s it!” I yell.

“That’s a brick wall,” says John.

“Okay! Then take this one! Here!”

“This is not an exit, this is a driveway. It’s very French. The highway looks like the driveway, and the driveway looks like—”

“Look out!” I yell as we swerve to avoid hitting a lorry that’s entering the triangle.

“Don’t overreact! Everything is fine. Stay calm.” Bass players are known for statements like this.

The French word for car crash is carambolage; it’s one of my favorite words, but I’d prefer not to use it today. Out of options, we exit the rotary on the same road we used to enter it, drive two blocks, perform the demi-tour—the French version of the U-turn—and miraculously find ourselves at 888 route de Riottier, the exact address of Monsieur Auray’s workshop.

You have reached your destination, says Kate. Bonne journée.

“Mon Dieu!” says John.

“Are you sure this is it?” I ask. I climb out of the car and brush baguette crumbs from my jacket. I had envisioned something quainter, perhaps a small chateau with hand-carved dwarves lining a cobblestone walkway leading to an antique oak door. But this place looks like the stark entrance to a French fort. No dwarves here. Later I will discover that many homes in Lyon are bleak on the outside but glorious once you get inside—it’s a style that goes back hundreds of years.

The back doors to the car open, and the kids tumble out and unfold themselves into upright positions. They remind me of pop-up tents. I do believe they’ve grown since the last rest stop.

“Isn’t this exciting?” I say.

“It looks like a jail,” says Curtis. “Do you think they have drinks at this place?”

“Look,” says Julia. “Pigeons!”

We park in front of a tiny plaque with Monsieur’s name and logo on it, and ring the bell.

We wait. John rings again. We can’t hear the bell ringing, so we’re not sure if it’s working. We wait some more.

“It is like a doorbell, only not a doorbell,” says John. He’s wound up, and I can understand why. He’s about to meet the man who will devote the next six months of his life to creating the bass of his dreams. I’m not so excited, mainly because we have just driven 800 kilometers and we’re standing in an alleyway in front of a cement shack. Maybe this is an elaborate French ruse.

John first met Jean Auray in 2008, at a bass convention in Paris. He played several of Jean’s instruments, one after another, and realized he had found a great luthier—an artisan who matched and even surpassed the work of many legendary bass makers. John’s search for an older instrument that would fit his needs was replaced with the thrill of having a new bass built to his specifications.

Monsieur Auray finally opens the door to his workshop and shouts out—in broken English—a few hearty words of welcome. We respond in broken French. We make introductions. He invites us inside. The chill of winter slips away as we walk into a carpenter’s golden oasis of wood and warmth. What a difference from the outside of the building. We climb a long curvy staircase, and it occurs to me that every bass-related business we’ve visited is up a flight or two of stairs. The place smells a little like a forest and a lot like varnish. A fine coating of sawdust covers every surface, and I’m reminded this isn’t a showroom, but a workshop. A heap of curlicue wood shavings is piled under the table, as if someone scalped Pinocchio and left the trimmings on the floor.

Madame Auray, a beautiful Englishwoman who was raised in Paris, greets us and serves coffee and biscuits. Her first name is Juliet. She is rail-thin and moves through the workshop like a nimble-footed cat. She picks up odd scraps of paper and used coffee cups while she talks to me and chats with the kids in both English and French. Curtis and Julia are learning French at school, but they’re shy about using it. I spent years speaking French in Haiti, but I sound like a cavewoman. Juliet glides back and forth between the two languages, making tiny corrections, introducing new words to us, and making sure John and Jean understand each other. In just sixty minutes of observing her, I know she’s the quintessential multitasking artist’s wife—interpreter, soother of the bruised ego, mother, mind reader, and bottle washer. I suspect she’s also the family accountant.

A wooden lion’s head with a menacing face—the topmost ornament of a bass that Auray is building for another musician—stands guard over the room. While John talks to Jean, I wander around the workshop with Juliet and peek into its attached rooms. Auray builds his own instruments, but he also repairs and sells other basses. The workshop has several smaller rooms attached to the main space, each one holding basses waiting to be repaired, basses that have been rescued from abusive homes, and a few basses that will never be played again but hold sentimental value. Even the basses with cracked bodies, rutted fingerboards, split seams, and broken tailpieces seem dignified. I hear the passion in Jean’s voice as he describes his craft. Even though I don’t understand much of his French, I know he agrees with me. The bass—strong and feminine and such an intimate part of my husband’s life—might be the most physically beautiful of all musical instruments.

John has chosen the Auray bass for its lush sound—clear and round and bottom-rich, perfect for a jazz musician. In addition, the Auray is compact and transportable, with a nontraditional removable neck. The flight case for the Auray bass, called the Nanoo, is still oversized according to airline regulations, but most carriers will take it. They won’t be happy about it, but they’ll take it.

“Never say you are traveling with the bass,” says Jean. “Say it is the cello-bass.”

“Cello-bass?” It is like a cello, but not a cello. I wonder what the baggage handlers will have to say about this.

“I will modify your bass with the removable neck, but first I must obtain the concept of your sound.” Jean’s favorite English words are modify and obtain; they are fancy words for his limited vocabulary, and he uses them with gusto. Fine-boned and handsome, Jean has thick dark hair, fluttering hands, and intense blue eyes, the kind of eyes that take in too much at once and make snap judgments—usually correct—about people and art and music. I get the feeling we’re being scoped out, interviewed and evaluated as potential adoptive parents for one of his bass children, and that one false move, one ugly American moment, and we’ll be back on the autoroute, squashed in the car with the collapsible kids, arguing with Kate, modifying our plans, and trying to obtain another luthier.

“Now we must obtain the measurements,” he says.

Curtis, Julia, and I sit in the corner with Juliet, eating our cookies and looking at pictures of other Auray basses.

John unpacks his older bass. Though it’s a nonpedigreed instrument, it has a nice voice that records well. It’s important for him to have a second bass that feels like this one, but with a more consistent tone.

“This is the sound I like,” John says, as he plays several passages. Jean cocks his head to one side, leans into the music, and smiles.

“Oui,” he says. “It sounds very beautiful. Only the new bass, the modified bass, perhaps she will be just as good. Perhaps she will be better.”

“Oui, oui,” says John. “I hope so.”

“This I think is not a problem,” says Jean. Both men are smiling. The challenge has been accepted, and if all goes well, both of them will win.

I walk over to Jean’s worktable and look through a large window. The soft browns and grays of the Lyon winter make a perfect backdrop for the aged tree in the center of the garden, whose twisted trunk and gnarled limbs stretch toward the corners of the stone terrace. There’s a song about this tree, and if I stand here long enough, I’m sure I’ll hear it.

“Oh,” says Monsieur. “You see the apricot tree!”

“It’s amazing,” I say. “Beautiful and ugly all at once.”

“Oui,” he says. “This is why we chose this place. For the tree.”

We are in the home of an artist. Who needs the dwarves?

**

John has been traveling the world with bass in tow for the last three decades. At the airport, some people point and stare and him. Others jump out of his way, hoping to avoid being run over by what looks like a coffin on wheels. Many feel obligated to make some sort of comment, which they obviously find clever at the moment. “You should have played the flute” tends to top the list.

There have never been any hard rules for bassists flying with their instruments. Sometimes there’s an extra charge of, say, 250 dollars. Sometimes it costs half of that. Sometimes it’s free. Sometimes they won’t take the bass at all.

One summer day in 1998 I’m put in charge of prechecking John’s bass from Cologne to London—no small task for a woman with fragile wrists and, as a professional pianist, a genuine fear of finger injuries.

“Don’t actually let them see the bass,” John says, doing that chop-chop thing with his hands that guys do when they’re giving instructions. “Park it really far away from the ticket counter, in a corner somewhere, and gesture toward it with large sweeping arm movements. Distract them—like a magician or hypnotist. And once you’re checked in, tip the porter really well so he wheels the bass out of sight before they change their minds.”

On the appointed day I park illegally outside of the airport terminal, unload the bass with the help of a janitor who has stepped outside for a smoke, and heave and push my way toward the British Airways check-in counter.

A woman wearing a giant backpack and pushing twins in a stroller the size of a Lexus SUV stops to open the door for me. “Wow,” she says. “And I thought I had it bad.”

“I should have played the flute,” I say.

I park the bass about twenty yards away from the counter—halfway behind a large pillar—and get in line.

Determined to use my Girl Power to get the job done, I’m wearing a black miniskirt and too much eyeliner. Turns out the check-in person is also using her Girl Power to keep refrigerator-sized objects out of the baggage hold.

“Checking any luggage today?” she says.

“Yes,” I say, using large sweeping arm movements, as previously instructed, and gesturing in the general direction of the bass.

“My God. What is that?”

“It’s a double bass.”

“Does that mean you’re checking two of them?”

“No. Just one. It’s a musical instrument.”

“Oh. A musical instrument.”

“Right. A musical instrument.”

Silence. She looks at her computer monitor. “Let’s see. On our list of accepted musical instruments, I have ‘small bassoon’—it’s obviously not that—”

“No, it’s not.”

“Banjo?”

“No.”

“Bass trombone, cello, or contrabassoon?”

“Uh, no.”

“Clarinet, French horn, flute?”

“No, no, no.”

“Guitar, oboe, saxophone, or trumpet?”

“Uh—”

“Viola in a rectangular case? Violin in a shaped case? Now, which one of the instruments on the list is yours? It looks like a bass tuba to me. Or is it one of those things they play in orchestras?”

Silence. Blank stare. It’s a standoff.

“It’s a double bass,” I say again. “It’s also called a contrabass or a bass violin.”

“Contrabassoon? That’s on the list.”

“No. Contrabass. Bassoon is a reed instrument.”

Silence.

“You blow through a reed instrument. Like this.”

Silence.

“The contrabass is a string instrument. With, you know, strings.”

More silence. She checks her computer monitor again. “Not on the list,” she says.

“Okay, some people call it an acoustic upright bass. Come on. It has to be somewhere on the list.”

A sneer, a sly smile, more silence.

“So sorry. It’s not on the list.”

“Bass tuba wasn’t on the list either, but you were willing to take it.

“No I wasn’t.”

“Yes you were.”

“No I wasn’t.”

I’m starting to sweat. “Okay then, can we just say it’s a contrabassoon?”

“So sorry, you’ve already told me it’s a double bass, and double bass is not on our list of accepted instruments.”

“Please. Can’t you make an exception?”

“No way, no how,” she says. “That—whatever it is—is huge. One could sleep in there.”

“Trust me, you wouldn’t want to,” I say. “You know, it’s really much smaller than it looks.”

“No. So sorry.”

“Look, I know it’s big, but this is really important. It’s not even my instrument. I’m checking it for my husband. He has a concert in London tomorrow.”

“Well, then, he should know better.”

“Please,”

“NO. So sorry.”

I cry, I plead, I demand to speak to the manager. It turns out she is the manager. I even attempt a casual bribe, flashing a few bank notes with that I’d-give-anything look. But nothing works. Loading the bass back into the car and driving it home is bad enough. Having to admit to my husband, who is returning from a gig in Switzerland later that night, that I’ve failed is worse.

We don’t blame the check-in people. No one teaches them about the double bass at airline school, where they are busy learning about exit-row safety procedures and gluten-free meals.

Another time a confused counter woman with a sympathetic smile decides the double bass is worth two overweight charges plus two oversize charges, a total of 300 dollars. She doesn’t tag it properly, and just as John and I are boarding the plane, airport security pages him and sends him to the tarmac. In front of several scowling orange-suited baggage goons wearing padded headphones, he unpacks the bass from the fiberglass trunk and strips off the soft cover. While they poke around and search through the flight case, he does what any respectable bassist would do. He plays.

“What did you play?” I ask when he finally boards the plane.

“‘Giant Steps,’” he says. “But they didn’t smile or anything. Maybe they’re not John Coltrane fans. They never even took off their ear protectors.” But we watch them load the bass onto the plane, so he must have done something right.

There have been missed flights and missing basses. How an airline could temporarily misplace a trunk the size of a Manhattan studio apartment is beyond me, but it has happened. We have logged many hours in the baggage area designated for weird luggage—the airport black hole where the orange-suit guys deliver tranquilized puppies in kennels, racing bikes in cardboard boxes, and musical instruments too big for the conveyor belt. The bass always comes off the plane last.

**

Several months into the bass-building project, Jean Auray sends us a photo of the curved part of the bass body resting on his worktable. The instrument, raw and relaxed, looks like a sensual and satisfied woman lying on her side, contemplating the casual miracle of the French spring. The apricot tree, flaunting green shoots that will soon burst open and protect the garden from the summer heat, peers back at the bass through the workshop window. If the bass is a woman, then this particular tree is most certainly a man.

“Wood,” Jean writes, “has an intelligence of its own and amazing qualities. One just needs to listen and treat it with respect, while understanding its strengths and weaknesses. Wood is elastic, but it’s solid and reactive, and capable of many sounds.”

Just like a good musician.

By the time an Auray bass is finished, Jean has shaved, carved, and sanded away eighty percent of the wood. This process—bringing the instrument to life—typically takes about 400 hours. The wood must rest and dry for at least a week after each adjustment so the bass can recover.

In France, even the musical instruments get vacations.

I glance at the photo again. Under the protective gaze of the apricot tree, the half-finished bass seems to anticipate the capable hands of the French artisan and the American musician. If all goes well, they’ll transform her from a silent piece of wood into an instrument that sings.

We wait. We receive more photos.

Two months later, Jean writes: “She played her first notes this afternoon. I think you will like her.”

Six months after our initial meeting with M. Auray, the bass is ready. Our son is on an exchange trip to South Africa and our daughter is visiting a friend in Sicily, so John and I travel as a duo to Lyon. It’s a leisurely trip, romantic even. We have just celebrated our eighteenth anniversary. That’s a lot of bass. But I guess I can’t get enough.

We arrive at Jean’s studio, climb the now familiar steps to his workshop, and watch as he removes the finished bass from its soft cover. I’m not quite sure what to look at—the bass, the bass maker, or the bass player. All three seem locked together and suspended in the noonish August light, an impressionist painting of human accomplishment and expectation. John takes the instrument and begins to play. To a musician, this is surely one of life’s most beautiful moments.

“Ah, yes,” John says.

“Oui,” says Jean.

I listen. This bass will age like a good relationship. It will open up, respond to its partner’s touch, and give back everything it gets. I choke back a few tears and accompany Juliet to her kitchen to help prepare the afternoon meal. Jean and John stay in the workshop to talk and make minor adjustments.

This is the first time I’ve been inside the Auray living quarters. On our previous visit we were confined to the workshop. The house, on the other side of a large garage area used to store aging wood, looks like the place I dreamed of finding when I was eighteen and reading about the French countryside. It’s an artisan’s paradise, with handcrafted kitchen counters and cabinets, an old dining table, and scarred wooden floors. In spite of the heat, the living room is comfortable and airy, with stacks of books in the corners and a cat curled on a threadbare antique chair.

Juliet tosses a salad while I slice a baguette. She tells me about her grown children, and I talk about Curtis and Julia. When the men join us, we sit together, drink wine, and dine on melon with prosciutto, quenelles, cheese, and a sausage from a local boucherie. Slow food, slow talk, slow music. This is the way I want to live.

“I must go feed the pigeon,” Jean says after the two-hour meal. “He fell from the sky and landed in front of our door.”

“When did this happen?” I ask. I wonder if it’s one of the pigeons Julia spotted six months ago.

“Yesterday,” he says. “On the thirteenth. We have named him Treize.” Jean grabs an eyedropper from a drawer. “I think Treize will be with us for a while. Right now he lives in a modified box, but soon I will be conducting the exercise class for him. I will throw him in the air, and he will fly. But maybe he will stay awhile and live in the apricot tree.”

“If I were Treize I would never leave this place,” I say.

We tour the garden, see the pond where Jean likes to swim in the afternoons after he has finished his day’s work, and retreat to the workshop where John learns how to dismantle the bass and pack it into the Nanoo flight case.

“Remember,” says Jean. “At the airport you should call her the cello-bass.”

We’re not flying today, we’re driving, and we must leave if we want to miss the autoroute traffic. John begins packing the instrument into the Nanoo for the trip home. Before he closes the case, Jean Auray rests his hand on the bass for a moment.

“It must be hard to say goodbye,” I say.

“I like to start anew again and again,” says Jean. “It’s my way of moving forward, not to get in a rut, a kind of challenge in the face of time—”

“I will take care of her,” says John.

“Please,” says Jean.

As we drive away, Jean stands by the front door, waving. It’s a sight I will never forget, the luthier releasing his work of art into the wild.

The transfer from one artist to the other is complete.

Turn right at the next intersection, says Kate.

“Turn that thing off,” says John. “I know where I’m going.”

Robin Meloy Goldsby is a Steinway Artist. She is also the author of Piano Girl; Waltz of the Asparagus People: The Further Adventures of Piano Girl; and Rhythm: A Novel.

Sign up here to receive Robin’s monthly newsletter. A new essay every month!